The aerobic threshold is an important marker of intensity for endurance athletes. It corresponds to the most important training zone to use in developing aerobic capacity, the key to all endurance activities that last over 2–4 minutes.

The aerobic threshold is the uppermost limit of exercise when the production of energy starts to become dominated by anaerobic glycolysis (sugars) rather than the oxidation (aerobic in nature) of fats.

It is the forgotten training threshold, overshadowed by its big brother, the anaerobic threshold. In this article, you will learn what the aerobic threshold is and why it is the key to building a robust cardiovascular engine and, sometimes, the key to improved strength gains.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Prior to reading this article, if you haven’t done so already, I highly recommend reading “The Beginners Guide to Cardio: The Ultimate Guide.” It’s the first article in the series and sets the scene and precedence for this piece.

Cardiovascular training, and in particular training the aerobic system, is one of the most poorly understood concepts in fitness. It is widely believed that anything that raises your heart can be deemed cardio.

This couldn’t be further from the truth. Just like strength training, you need to obey the laws of physiology and work in conjunction with the CNS (Central Nervous System). There’s a system and process to maximally develop the cardiovascular system, and that process begins by maximally developing your aerobic threshold.

Having read our previous article, “The Beginners Guide to Cardio,” you should be aware that to maximize your cardiovascular capacity, you must first maximize your aerobic threshold.

It’s worth reminding ourselves of our model of cardiovascular development:

“If you don’t maximally develop your aerobic energy system first and have sufficient levels of strength, you will never truly maximize your anaerobic threshold.”

Today’s article is all about the aerobic threshold: what it is, why you need to train it, and more importantly, how you can test your own Aerobic Threshold and train it. Let’s dive in.

What Is the Aerobic Threshold?

The aerobic threshold is the uppermost limit of exercise when the production of energy starts to become dominated by anaerobic glycolysis (sugars) rather than the oxidation (aerobic in nature) of fats.

It is an important marker of intensity for endurance athletes. It corresponds to the most important training zone to use in developing aerobic capacity. Without first maximizing your aerobic threshold or base levels of strength, you will never truly maximize your anaerobic threshold or VO2 Max, the gold standard indicators in measuring one’s potential cardiovascular performance.

In scientific terms, the aerobic threshold is at the point that blood lactate begins to rise above the normal resting level of 2mmol/L (millimole per litre).

It’s important to understand the role of lactic acid, which is so often seen as the cause of poor cardiovascular capacity. Lactic acid only appears in the body when the body can no longer work aerobically, and lactic acid begins to accumulate through anaerobic glycolysis.

The two golden rules of developing the cardiovascular system are:

- Reduce the production of lactate by having a higher aerobic threshold.

- Increase the rate of lactate removal from the working muscles by having a fully functioning anaerobic system.

The first rule is all about maximizing your aerobic threshold. The second rule is about maximizing your anaerobic threshold. Both need to be trained very differently, but both are key to maximizing the cardiovascular system.

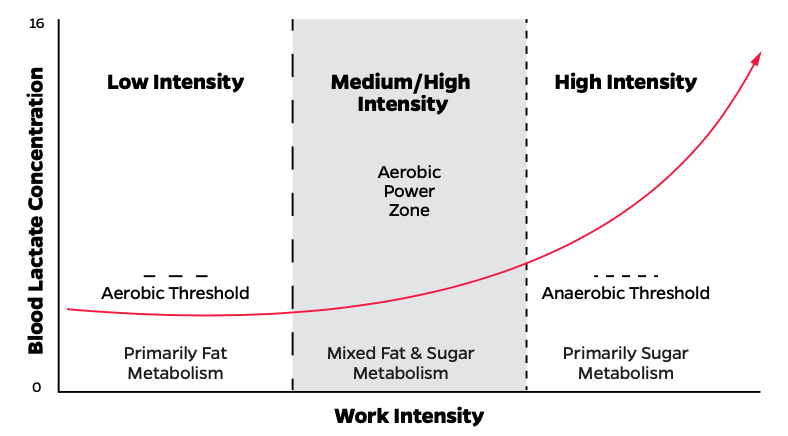

The image below illustrates where the aerobic threshold sits and how blood lactate concentration starts to increase as workout intensity increases. It also illustrates the primary fuel sources at each level.

As you can see in the image, there are essentially three zones of training: below the aerobic threshold, a mixture of both aerobic and anaerobic zones, and then finally the zone above the anaerobic threshold.

One of the biggest problems we see with everyday athletes of all abilities and ages is that they don’t spend time developing either aerobic or anaerobic threshold specifically. Instead, they spend the vast majority of their time training in what we call “the black hole of death,” that middle zone of nothing. The middle zone uses both glucose and fat for fuel.

The secret of the world’s elite endurance athletes is that they close the gap significantly between the aerobic threshold and the anaerobic threshold. Most elite endurance athletes have less than a 10% difference between the two. This means they can perform faster, for longer, and more frequently as they work below their aerobic threshold, using their fat stores as their primary fuel source.

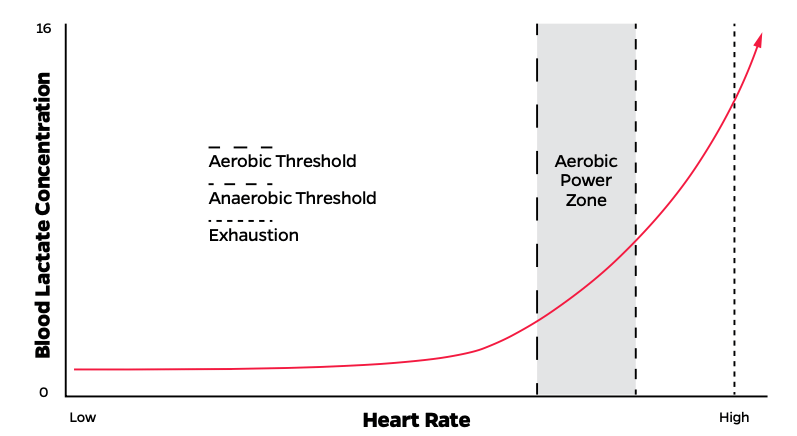

The image below illustrates an example of an advanced endurance athlete with a high aerobic base. Notice how they can work out harder, for longer, before blood lactate starts to accumulate. Their middle zone of death is much smaller, and therefore, they spend less time using glucose (sugars) for energy and more time using fat.

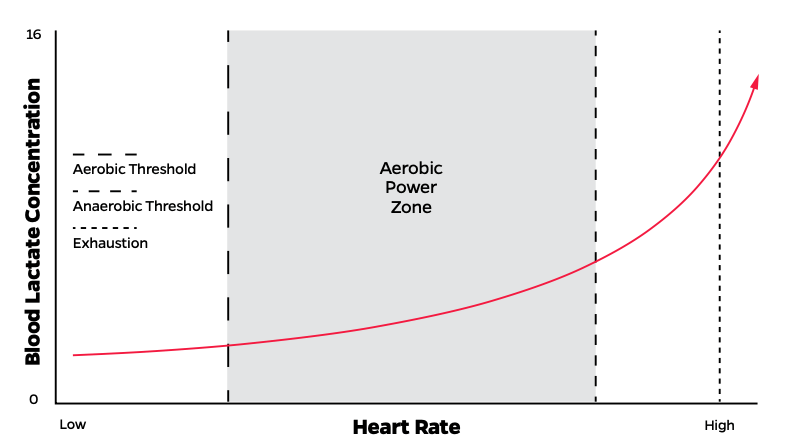

On the flip side, the following picture shows somebody who suffers from ADS (Aerobic Deficiency Syndrome). They have a very poor aerobic threshold, and their middle zone of death) is considerably larger. This means they will tire much faster than the advanced athlete above.

I would argue that the vast majority of the world’s population suffers from Aerobic Deficiency Syndrome. We are so wired to believe that we should work out harder for longer, just like the sizzle reels of elite athlete training videos, that we often miss the hard work, dedication, and patience it requires to really maximize your true athletic potential.

What Is Aerobic Deficiency Syndrome?

Aerobic Deficiency Syndrome (ADS) is one of the most common athletic issues we see in those people who work with us for coaching and training. It’s not a disease, so don’t worry about that. It’s a term first coined by Dr. Phil Maffetone in the 1980s.

It’s a reversible condition that results from doing too much anaerobic or high-intensity exercise. People who exhibit it often have high-level anaerobic capacities from years of working out at these higher intensities.

They feel athletic, fit, fast, and strong. But their aerobic base is completely underdeveloped—even non-existent. It means they have a huge middle zone of death, as illustrated above, and are extremely good at exercising in this area.

This condition can be devastating for endurance athletes since it contributes to reduced endurance. It leads to quickened fatigue, loss of aerobic speed, and overtraining.

The first and most obvious sign of Aerobic Deficiency Syndrome is chronic fatigue.

Chronic fatigue is typically due to the lack of aerobic base, resulting in greater reliance on glucose (sugar) for energy—not just during workouts but at all other times of day and night.

Other symptoms of ADS include increased body fat. Less fat is used for energy and more remains stored throughout the body, which is also strongly associated with chronic inflammation.

Essentially, aerobic deficiency syndrome means that the anaerobic system has to work far harder than it should to keep the body going. The body is simply not as efficient as it should be. This typically means that heart rates are elevated, resulting in higher levels of stress.

This not only affects athletes but everyday people, too. Just think about it, the lower your aerobic threshold, the less energy you have throughout the day to complete routine tasks, and the more time it takes you to recover from completing these tasks.

Having a high aerobic threshold allows you to perform more tasks, better and faster, and it allows you to recover faster. As people move less and less, the harder these routine tasks become because humans are becoming severely undertrained and are predominantly relying on their glucose (sugar) levels to support them through the day.

Can you see now why so many people reach for those sugary energy drinks daily?

How to Test Your Aerobic Threshold

We believe determining your aerobic threshold is THE MOST IMPORTANT FACTOR in cardiovascular training. It starts as your foundation, your basis from which all other training plans and programs are written.

So how do we test for your aerobic threshold?

Remember, this is very different from testing your anaerobic threshold, so please don’t get confused here. The aerobic threshold is the point when lactate starts to build above its normal resting level. It’s a far easier test and is almost done at comfort levels.

The only true method of testing your aerobic threshold is to do so in a lab with expensive equipment performing the gas exchange test. There are very few labs around the world that can do this, and it is expensive to administer.

I would say this test is for elite athletes only because at the elite levels, the 1% differences count.

But for us mere mortals over thirty, we can use three simple methods that anybody can do:

- The Talk Test:

- The Breath Test

- The MAF Method

#1 – The Talk Test

We ask people to perform some kind of cardiovascular exercise (rowing, running, walking, cycling, etc.) If they cannot hold a normal conversation while performing this type of exercise, they are working above their aerobic threshold and need to slow down to continue working below their aerobic threshold.

#2 – The Breath Test

We ask people to perform some kind of cardiovascular exercise (rowing, running, walking, cycling, etc.) While performing this type of exercise, if they cannot comfortably breathe through their nose while keeping their mouth closed, they are working above their aerobic threshold and need to slow down to continue working below their aerobic threshold.

We often ask people to perform this type of exercise with water held in their mouth to ensure nasal breathing is maintained throughout. That way we can ensure aerobic threshold training is maintained. After the MAF method, this is our preferred method if no heart rate monitor is available.

#3 – The MAF Method

The MAF Method (Maximum Aerobic Function) is our default and preferred method for aerobic threshold training. It requires a heart rate monitor. Devised by Dr. Phil Maffetone in the 1980s, it is a simple formula of subtracting your age from 180.

Depending on your training history, Dr. Maffetone recommends the following modifications to the formula:

- If you’re recovering from an injury or get sick more than two to three times per year, subtract an additional five.

- If you’ve been training for more than two years and showing regular progress, then add five.

Once you have determined your score, you then perform your exercise at this intensity and just below (no more than 10 beats below), never above. It’s not the perfect method, but for sake of simplicity and time-tested results with numerous world endurance champions, you simply can’t go wrong with this method.

MAF Method Working Example:

Let’s use me as an example. I’m 37 years old: 180 – 37 = 143

I have no history of illness or disease and have been training regularly for over two years. Therefore, I would add 5 beats.

My final score is 148.

Therefore, if I was performing cardiovascular exercise with the sole intent of improving my aerobic threshold, I would ensure my heart rate never exceeded 148. But I would try to keep it between 138 and 148 to maximize the development of the aerobic threshold.

Training Working Example

Let’s apply this to a training example; the easiest would be running. If I was to go for a 60-minute run, I would make sure to adhere to one of the following:

- Running at a pace at which I can comfortably hold a conversation.

- Running at a pace at which I can comfortably breathe through my nose.

- Running at a pace at which my heart rate never exceeds 148 and never drops below 138.

If at any time I couldn’t adhere to any of these methods, I would simply slow down. Perhaps I would slow down so much that I would have to walk, which is a very common and regular occurrence when first applying this methodology.

It’s very different to training the anaerobic system. This is all about training well within your comfort zone.

How to Train to Maximize Your Aerobic Threshold

There’s no easy way to say this, but the key to building your aerobic threshold is volume… volume, volume, volume of sub-aerobic threshold training that will allow us to build up our aerobic speed and make our movement economy more efficient in terms of technique and metabolism.

We have to re-train the body to prioritize using fat as the primary fuel source for endurance-based activities, and that means spending hours and hours working at below your aerobic threshold.

Remember, you will never maximize your cardiovascular potential without first maximizing your aerobic threshold. Having a robust aerobic system is paramount before we dive into developing your anaerobic threshold. A certain level of strength is required to allow us to go deep enough into this system to elicit the correct dose response.

When we talk about volume, the question we always get asked is “How much is enough?” It’s simply impossible to answer because everybody has a different capacity for this type of work.

A warm-up for an elite athlete may complete overload a novice trainee, and what constitutes enough for one intermediate athlete may completely overload another. When you work on building the aerobic threshold, there isn’t a one-size-fits-all approach. It has to be unique to the individual in question.

If you want to build a truly robust aerobic threshold, you need to look at it from an annual training perspective and understand that volume and consistency is key to development.

As a novice, you want to build to a minimum of 400 hours of training time each year working on the cardiovascular system, not including strength or movement-based workouts. That’s roughly 7–8 hours a week dedicated to cardiovascular work.

If you’re a true beginner, 100% of your weekly training time will be aerobic in nature. That means NO HIIT workouts. Remember, aerobic threshold development and strength training come first, and you need to earn the right to do HIIT.

At the top end, you’re looking to build to 800+ hours of cardiovascular work each year. This is what the elite level men and women do, and it gives you an idea of what it takes to get to that level.

You may be reading this and thinking I have no chance of hitting 400+ hours of training. You might be slightly deterred. I’m sorry to be the bearer of bad news, but this is what it takes to become a serious everyday athlete.

You simply can’t do it by swinging a few kettlebells a few minutes each day or doing 10-minute booty blasts. Your results will be directly proportional to the amount of work you put in, and building the cardiovascular engine and developing your aerobic threshold takes time, effort, and dedication.

But I promise you, it’s worth it in the long run.

Where to Start to Develop the Aerobic Threshold

If you’ve gasped at our 400 hours a year standard, please don’t be intimidated. It wasn’t put here to intimidate or frighten you. It can easily be achieved if you have the right mindset and build a lifestyle around that positive mindset.

For beginners, the first step to building your aerobic threshold is quite simply to walk more. It really is that simple. Walk more. Walk to work. Go for evening walks. Go for weekend hikes. Hit your 10k steps a day. For most people, this is the very best way to start and the safest.

If you’re new to aerobic training, you can’t jump into running 400+ hours a year if you’ve never run a single hour. You have to build up to it. Safety and longevity first. Your body won’t be ready for it. You are more likely to break down along the way.

Once you have built up your walking abilities, maybe start to introduce run-walks. In the gym, choose the rower and assault bike over free-weights from time to time. Try and build up to 60-minutes of continuous work on these machines while obeying the laws of the talk test, breath test, and MAF Method described above.

For intermediate and advanced athletes, take running and rowing as an example. Embrace the MAF method. Build the engine on these long slow runs, keeping below your MAF heart rate.

You are highly likely to suffer from ADS (Aerobic Deficiency Syndrome), which means the pace of your runs and rowing will be frustratingly slow! I know exactly how you will feel – embarrassed and like it’s a waste of time.

But trust me, stick with it. Elite marathon runners can run sub 5-minute miles below the aerobic threshold for mile after mile. Doing aerobic threshold work does not mean going slow. Far from it. You just have to earn the right to build it.

And it takes time, lots of it. But stick with it, and you really will start to train like an elite athlete. Aerobic threshold training makes up approximately 85% of their total annual training plans.

Why? Because they know what you don’t. You need to build a solid foundation for the rest of your cardiovascular system. And that foundation is aerobic speed. So, stick with it and give it time. You can thank me later. You can also join our online support group of training members in the low heart rate training group.

Closing Thoughts

The aerobic threshold is the most important concept to grasp when training the cardiovascular system. Most of the world’s population arguably suffers from Aerobic Deficiency Syndrome through poor choices of cardiovascular training or simply a complete lack of training awareness and ability.

It’s important to remember that if you don’t maximally develop your aerobic energy system first and have sufficient levels of strength, you will never truly maximize your anaerobic threshold. The key to training the aerobic threshold is volume. There are no shortcuts, and there is no easy way out.

But it doesn’t have to be difficult. The aerobic threshold is built at a low intensity. Apply either the talk or breath test or our preferred choice the MAF method to ensure you train below this threshold at all times. Either way, you must train it for the sake of your own health and athletic performance.

Here’s to a better aerobic threshold.

FAQ

What is the Aerobic Threshold?

The aerobic threshold, also known as the first ventilatory threshold or VT1, refers to the exercise intensity at which your body starts to produce lactic acid faster than it can be removed, causing it to accumulate in the blood. At this point, you switch from mainly aerobic metabolism, which uses oxygen, to anaerobic metabolism, which doesn’t require oxygen. It’s the point at which exercise begins to feel noticeably more difficult.

Why is Understanding Your Aerobic Threshold Important?

Knowing your aerobic threshold is vital for training effectively. Training at or slightly below your aerobic threshold can improve your endurance and the efficiency of your cardiovascular system. By training at different intensities relative to your aerobic threshold, you can focus on different aspects of fitness, like endurance, speed, or strength, depending on your goals.

How Can You Determine Your Aerobic Threshold?

The most accurate way to determine your aerobic threshold is through a lab test, like a VO2 max test or a lactate threshold test. However, a practical way to estimate it is by using the ‘talk test.’ Your aerobic threshold is typically the exercise intensity at which you switch from being able to speak comfortably to noticing your speech start to break up as your breathing becomes heavier. This is a rough estimate and individual results may vary.

What is Aerobic Deficiency Syndrome (ADS)?

Aerobic Deficiency Syndrome (ADS) is a condition typically found in athletes, especially endurance athletes, where the aerobic system is underdeveloped compared to the anaerobic system. This imbalance is often due to an excessive focus on high-intensity training without enough low-intensity, aerobic exercise. It can lead to early fatigue and less efficient performance.

What are the Implications of Aerobic Deficiency Syndrome for Athletic Performance?

In the case of ADS, the athlete’s aerobic system can’t adequately supply energy during high-intensity activities, leading to early reliance on the anaerobic system. This results in quicker fatigue, as the anaerobic system is less efficient and cannot sustain energy production for long periods. Therefore, athletes with ADS may find their performance in longer-duration activities diminished.

How can Aerobic Deficiency Syndrome be Prevented or Corrected?

To prevent or correct ADS, athletes should ensure they are incorporating sufficient low-intensity, aerobic training into their routines. This helps stimulate adaptations that improve aerobic metabolism, such as increased capillary density and greater mitochondrial volume. A well-rounded training plan that develops both the aerobic and anaerobic systems can help maintain balance and enhance overall performance. As always, it’s recommended to work with a knowledgeable coach or trainer to develop an appropriate and personalized training plan.

What Are Examples of Aerobic Threshold Activities?

Aerobic threshold activities often include steady-state exercises like jogging, light cycling, or brisk walking. These activities are performed at a pace where breathing remains even and the body primarily utilizes oxygen for energy production.

What Is the Relationship Between Aerobic Threshold and FTP (Functional Threshold Power)?

The aerobic threshold is typically below FTP. FTP represents the highest power level a person can maintain for an hour without fatigue. The aerobic threshold is the point before reaching lactic acid build-up, allowing for longer durations of exercise.

What Are the Benefits of Training at the Aerobic Threshold?

Training at the aerobic threshold improves cardiovascular health, increases stamina, and enhances the body’s ability to utilize fats as a fuel source. It allows athletes to exercise longer with less fatigue.

Does Aerobic Threshold Heart Rate Change?

Yes, the aerobic threshold heart rate can change based on factors like fitness level, age, and training. As one’s fitness improves, their aerobic threshold heart rate may increase, allowing them to work harder before lactic acid build-up. Regular training can also help in optimizing it.

This article was fascinating, thanks so much for offering it for free. I will share with athletic friends. I used to be a competitive swimmer but after a viral illness I developed a bad case of myalgic encephalomyelitis, or ME/CFS. It is believed this is essentially a post viral mitochondrial disease similar to Long Covid. I currently use a Polar M430 watch to monitor my heart rate and have set an upper limit alarm to alert me when I get to 95bpm. Sustained activity beyond this level produces a horrible flu-like illness that can last for weeks. But here is my question. Everyone in the ME community refers to this ‘do not pass’ point as ‘anaerobic threshold’. But it would seem from your article that this is actually the ‘aerobic threshold’. In ME/CFS we have a damaged aerobic system due to mitochondria dysfunction, and we get trapped in the anaerobic system and produce too much lactic acid. I liken it to ripping down the highway stuck in first gear. So isn’t it the aerobic threshold I need to avoid? I will never get to the upper anaerobic threshold unless and until I recover completely. I remember using this in swim races at the end as I would not even take a breath for the final 15 meters.

Hi James,

Is there any harm/benefit to training my aerobic threshold if I include higher-effort runs into my treadmill routine (this is partially to break the monotony). I like to warm up, do a slow jog (~14:00 mi) for a while, then try to run at a 8:30mi to 7:30mi pace (7-8mph) for at least 5 minutes to burn myself out, then spend the rest of my run at a light pace where I can keep my mouth closed. The 5-minute KM is absolutely an effort for me – I’m not going to pretend I know whether it’s in the mixed zone or anaerobic zone, but if i try to go at 8mph I usually can’t manage the full 5 minutes- but it makes it easier to stay up high near my calculated aerobic threshold while at around a 13:00/mi walk/run pace.

I would do the zone 2 work first, then anything else after you wnat if if it feels good. I wouldn’t return to the zone 2 easy work after though… as it then gets mixed results imo.