What are some good strength standards that everyday people should aim for?

You see, everyday athletes train strength to improve quality of life, enhance performance in their chosen sport or sports, and to prevent injury. There is a significant difference between being gym strong and real-world strong.

Lasting results and athletic performance require you to put in the time and effort both in and out of the gym. There’s no getting away from it and there are no shortcuts. Training for the sake of becoming stronger in the gym isn’t an option for us.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Back in the day, I used to engage in the same gym conversations: How much can you bench? What’s your deadlift? You squat how much? I thought the answers to these questions were what mattered to my own fitness and that of my clients.

Here’s the secret: Those benchmarks don’t matter for everyday athletes. Thousands of studies attempt to answer the question of how strong athletes need to be. The common answer between them all is improving max strength has a positive effect on quality of life, athletic performance, and injury prevention.

Strength matters. There. I said it.

As mainstream media force feeds us a diet of high-intensity interval training (HIIT) and 19-year-old scantily clad influencers on Instagram post one sexy feat after another, the concept of what strength training really is has become blurred. Strength training doesn’t always turn you into a sweaty mess on the floor; it is far more complicated than that.

Strength in its truest form is largely neurologic in nature, not metabolic. For humans to produce force, our nervous system activates a muscle or group of muscles to cause a contraction. Strength is the ability to recruit a large number of muscle fibers and produce as much tension throughout the body as possible.

In a strong body, the nervous system activates a large percentage of muscle fibers during a given contraction. In a weak body, even though the muscle itself may appear to be the same size, the nervous system is less able to activate as many muscle fibers and, therefore, less force is produced.

This is the difference between real world strong and gym strong. I’m often asked how much strength is enough? The answer is no one really knows because it depends.

When discussing strength training, we need to understand two key terms: General Strength and Specific Strength. General Strength is not sport specific, though it is the base which supports Specific Strength training. It’s where 90% of everyday athletes should spend most of their training time.

Specific Strength is sport specific, meaning it has a direct bearing on an athlete’s performance in a particular sport. Most everyday athletes over thirty like to think they’re elite athletes (don’t worry; I do too!) and skip General Strength training principles all together to follow Specific Strength training regimens, often to disastrous consequences. In other words, we like to run before we can walk.

The big problem here is that nobody really knows what General Strength standards really are. Nothing is clearly defined for us everyday athletes, and without standards that are easy to follow and applicable, we end up formulating our own standards. That’s where Strength Matters comes in.

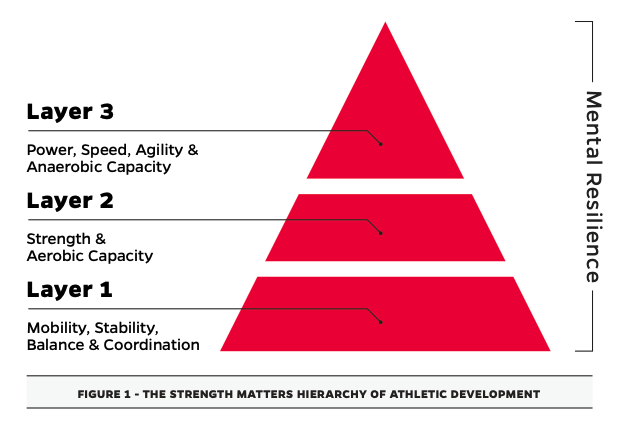

The Strength Matters Hierarchy of Athletic Development

Let me introduce you to The Strength Matters Hierarchy of Athletic Development to show you where General Strength fits in:

Layer 1 is the foundation of the system. We need a base level of mobility, stability, balance, and coordination first. If we’re deficient in these areas, progress will be slow and the risk of injury heightened. This is where we assess your movement score.

Layer 2 is strength and aerobic capacity. Once we have our Layer 1 base, we start to build onto it with basic strength and aerobic capacity work. Layer 2 is where General Strength comes into play and is roughly scored.

Layer 3 is the sexy layer, and advanced athlete territory. It’s the layer everyone wants to jump to and includes power, speed, agility, and anaerobic work (HIIT) that contribute to Specific Strength. It’s also the layer that comes with the most risk. If you’re deficient in any of the components of Layer 1 and Layer 2, it will show up here. This means injury is more likely and peak athletic performance is hindered.

The Strength Matters Hierarchy of Athletic Development and the everyday athlete scoring system are vital tools for us to identify areas of weakness that need to be addressed and highlight the need to train our weaknesses.

It’s a system that leaves nothing to chance. A system to help people reach maximum physical potential. A system to help everyday athletes reduce the risk and likelihood of injury. A system that knows exactly what your weaknesses are and tells us how you should train them.

How We Assess General Strength

Now that you understand our logic and system of training, let’s address strength directly. General Strength falls under Layer 2 of the Strength Matters Hierarchy along with aerobic capacity.

Both components are divided further into sub layers – we refer to them as Layer 2.1 and Layer 2.2. If someone was to complete our entire system of assessments this is how it would look:

- Step 1: Health

- Step 2: Layer 1

- Step 3: Layer 2.1

- Step 4: Layer 2.2

- Step 5: Layer 3.1

- Step 6: Layer 3.2

Health to Layer 2.1 is completed by everyone. After Layer 2.1, you must earn the right to continue the process – it’s like a secret door to a new world of assessments on successful completion of each layer.

In order to pass through Layers 2.2, 3.1, and 3.2, you must have scored over 75% in all four areas of fitness (Health, Movement, Strength, and Cardio). Everything must be in balance.

The Layer 2.1 strength assessments test basic strength, balance, mobility, and stability. They start by looking at the holy trinity of strength (grip, abs, and glutes) because a weak link in any of these three will result in poor results long term.

We then progress to assessing single-leg squat strength in combination with balance, mobility and stability – as highlighted by the Rear Foot Elevated Split Squat, the Airborne Lunge and Advanced Balance tests.

If any of these aren’t completed, we know your body is lacking in lower body strength and doesn’t own mobility and stability. It then becomes clear we have some work to do to improve these areas.

The only test I feel needs explanation in Figure 3 is the advanced balance test. Quite simply, stand on one leg in shoes with laces and socks.

Whilst standing on one foot, unlace the shoe, take the shoe and sock off, and put them both back on. Finish by lacing the shoe up without falling over or placing that foot on the floor at any point.

It’s a simple yes or no scoring system. Give it a go after reading this.

If any of these tests are a struggle, you don’t advance to Layer 2.2 and most certainly not to anything in Layer 3. Even though I know you want to sneak up there. Once you pass everything under health, movement, and Layer 2.1, you can proceed to Layer 2.2.

The Layer 2.2 strength assessments test the foundational skills of a General Strength training plan. We approach programming always with the mindset of training the seven human movements. Layer 2.2 strength assessments ensure that they are all covered. They are:

- Locomotion

- Push

- Pull

- Hinge

- Squat

- Rotate

- Anti-Rotate

The standards listed below are what you need to do to get a perfect 100% strength score across the board. We do operate with a traffic light system (red, amber, green) with some of the tests, but explaining that is a little too complex for this article.

Layer 2.1 Strength Standards

| Test | Directions | Standards |

|---|---|---|

| Straight Arm Plank | With your arms straight, hands positioned under the shoulders, and your feet together, hold the plank position for as long as possible. | 2 Minutes |

| Glute Bridge | Lie face up on the floor, with your knees bent and feet flat on the ground. Keep your arms at your side with your palms facing up. Lift your hips off the ground until your knees, hips and shoulders form a straight line. Hold the bridged position for as long as possible without breaking that straight line. | 2 Minutes |

Airborne Lunge (Left/Right) | Stand on your LEFT foot and bend your RIGHT knee, bringing your heel back up toward your bum, extending your toes back behind you. Imagine you’re performing a reverse lunge, except drop your RIGHT knee to the ground and allow the instep of your RIGHT foot touch to touch the floor. Gently push off your instep and come back up to standing. Repeat the process. | 8 Reps |

Rear Elevated Split Squat (Left/Right) | Using bodyweight only, stand in a lunge position with your LEFT foot forward and your RIGHT foot back on bench or box that’s approximately the height of your knee. Bend your front LEFT knee to lower into the lunge until thigh is parallel to ground. Extend the hip and knee to drive up to the start position. Repeat the process for eight reps. | 8 Reps |

| Straight-arm Bar Hang | Use a secure overhead bar. Grip the bar with an overhand grip (palms facing away from you). Aim to keep your arms shoulder-width apart. Keep your arms straight. Don’t bend your arms and stay relaxed. Hang for as long as possible. | 1 minute |

Layer 2.2 Strength Standards

| Test | Directions | Standards |

|---|---|---|

| Box Crawl | All you need for this test is your bodyweight, a timer, and an object on the floor. Get on floor in a table top position and lift your knees off the ground. Crawl around the object as many times as possible without pausing or placing your knees back down on the ground. The one caveat: You must change direction after every lap. | 5 Minutes |

| Push-Ups | How many push-ups, every 3 seconds, can you perform? | Men: 40 Reps Women: 24 Reps |

| Flexed Arm Hang | Using an OVERHAND grip, grip the bar with both hands shoulder-width apart and get into the topmost pull-up position, with chin above the bar. Without any support other than your hands, simply try to hold your chin above the bar for as long as possible. | Men: 60 Seconds Women: 30 Seconds |

| Chin-Ups | Use an underhand (supinated grip). Set a timer to beep every 5 seconds. Start in the dead hang position and perform one chin-up (if possible) and return to the dead-hang position. | Men: 6 Reps Women: 3 Reps |

| Pull-Ups | Use an overhand (pronated grip). Set a timer to beep every 5 seconds. Start in the dead hang position. Perform one pull-up (if possible) and return to the dead-hang position. | Men: 6 Reps Women: 3 Reps |

| Deadlift | Men: 1.5 x Bodyweight Women: 1.25 x Bodyweight | 5 Reps |

| Backsquat | Using a conventional barbell load the barbell so it weighs the same as your bodyweight. Perform as many reps as possible, up to a maximum of five, ensuring you go below parallel on each repetition. | 5 Reps |

| 75% Bodyweight Rear Elevated Split Squat (Left/Right) | Choose two weights equalling 75% of your bodyweight. Perform eight reps on your LEFT side. Rest one minute, and repeat on the RIGHT side. | 8 Reps |

| Turkish Get Up (Left/Right) | Choose your weight and perform five continuous Turkish Get Ups on your LEFT side. Rest one minute prior to testing your RIGHT side. Standards: Men ≤ 68kg @20kg, ≤ 100kg @24kg, > 100kg @28kg Women ≤ 59kg @12kg, > 59kg @16kg | 5 Reps |

| 75% Bodyweight Farmer Carry | Pick up two weights equalling 75% of your total bodyweight and walk for 90 seconds WITHOUT having to put either weight down or re-gripping at any point. | 90 Seconds |

| Airborne Lunge Level 2 (Left/Right) | Stand on your LEFT foot and bend your RIGHT knee, bringing your heel back up toward your bum, extending your toes back behind you. Imagine you’re performing a reverse lunge, except drop your RIGHT knee to the ground but DO NOT allow your RIGHT foot to touch the floor. Push off your front foot without your back foot touching the floor and come back up to standing. Repeat the process on the other leg. | 8 Reps |

I want to dive into our more absolute tests or the ones that are a simple pass or fail. They are:

- 75% Bodyweight Farmer Carry

- 75% Bodyweight Bulgarian Spit Squat

- Box Crawl Test

The 75% Bodyweight Farmer Carry

This test is as simple as picking up two weights equaling 75% of your total bodyweight and walking for 90 seconds WITHOUT having to put the weight down or re-gripping at any point.

This is one of the most important tests we do, and shows us whether or not you’re able to maintain alignment with integrity under load.

Think of this test in terms of a car: If one component of a car must fail while driving, we would hope it’s the engine before the brakes. In terms of your body, we would hope that the working muscle (the engine) fails before your postural stabilizers (the brakes).

Working muscles without using postural stabilizers leads to poor alignment and poor stability, yet most people train their lifts more than their carries.

Essentially, people never service their brakes! The ability to maintain integrity under load is more important than the ability to lift load.

We need functional brakes before we fire up that engine. Less than 10% of people pass this test on the first attempt and usually take months of training to do so.

The 75% Rear Foot Elevated Split Squat (RFESS)

The test is completed by choosing two dumbbells or kettlebells equaling 75% of your bodyweight. You perform eight reps on your left side, rest one minute, then repeat on the other right side.

There have been huge debates as to what type of squat improves athletic performance the best: Unilateral (single leg) or bilateral (both legs). I see the need for both but one thing I’ve learned from my years as a coach is the bar always wins.

You can easily keep adding weight until you eventually break down, whether that be with the deadlift or squat. I’ve seen it time and time again with injuries from friends, peers, and colleagues who kept loading weight and not servicing their postural stabilizers (the brakes) first.

I’ve never seen anyone herniate a disk doing unilateral squat work. The RFESS develops balance, stability, and hip flexibility, along with strength.

You can apply huge weights to your leg muscles with limited spinal compression. Since there’s a limit to just how much weight you can load, is has built-in safety measures.

We see the RFESS as a gateway to heavier loads and barbell/kettlebell technique work that also provides the foundational single leg strength needed to excel at activities such as running.

Similar to the farmer’s carry, we view this as a key milestone in the strength development of everyday people.

The Box Crawl Test

“If it looks right, it flies right.” I’m not sure where this quote comes from, but I first heard it from track and field speed coach Charlie Francis. It sums up the box crawl test nicely; you can see who’s going to pass or fail this test in a matter of seconds. All you need is your bodyweight, a timer, and an object on the floor.

With your knees elevated, crawl around this object as many times as possible without pausing or placing your knees back down on the ground. The one caveat: You must change direction after every lap.

The Box crawl test is one of the best tests I’ve ever seen for core, motor control, reflexive strength, and gait pattern. It will tell us everything about your coordination, core control, and shoulder stability whilst under load and fatigue.

If there’s an issue here, just like farmer carry test, there’s a problem with your body’s brakes, and you know now how important the brakes are. Five minutes is a very long time for some but, in an ideal world, we’d like to see these times closer to 10 minutes.

Final Thoughts

Most of these assessments are achievable by everyday athletes with adequate training. There’s nothing elite about these numbers but they form the basis of good General Strength standards. Hitting these types of numbers will put you in good stead for the rest of your life, even if you have no desire to become an elite athlete.

If you do aspire to venture into the elite fields, it provides a solid starting point to make sure you have the basics in place before attempting anything more complex. Never skip the basics in strength training; I promise you it will save you from years of hurt and frustration, something, I’ve learned the hard way.

FAQ

What Are Good Strength Standards?

Good strength standards differ based on various factors. Typically, for an average male with some resistance training experience, squatting 1.5x body weight, bench pressing 1x body weight, and deadlifting 2x body weight are seen as solid benchmarks. For females, 1x bodyweight squat, 0.75x body weight bench press, and 1.5x body weight deadlift can be good initial standards. Of course, age, experience, and specific sports can change these guidelines.

Are Strength Standards Accurate?

While strength standards provide a useful benchmark for assessing relative strength, they might not capture an individual’s full potential or limitations. They are generalized based on collected data, but individual variations due to genetics, limb length, training history, and nutrition can impact performance. It’s beneficial to use them as guidelines but not absolute indicators of one’s capabilities.

What Are the Strength Standards for Lifting with Body Weight?

Lifting with body weight as a benchmark has been a staple in resistance training. For many, a bodyweight bench press, 1.5x bodyweight squat, and 2x bodyweight deadlift represent commendable benchmarks. Achieving these means one is generally stronger than the average person. Still, depending on one’s training focus and sport, these numbers can vary.

What Is the Benchmark for Strength?

A benchmark for strength isn’t solely about the weight on the bar. It’s about functional strength, muscle balance, and injury prevention. The ability to perform key compound movements, like squats, deadlifts, and presses, with good form is crucial. For those who train consistently, achieving and surpassing intermediate strength standards—like a double bodyweight deadlift or a bodyweight overhead press—signals a good strength foundation.